By Amir Oskouei July 29, 2025

Founder, Amir Textiles & Rugs – Researcher & Collector of Turkic Woven Art

Introduction: The Forgotten Totem

Across the highlands of the Caucasus, the plateaus of Iran, and the steppes of Central Asia, one creature has walked beside nomadic peoples for millennia — not merely as livestock, but as a spiritual companion, a provider, and a sacred emblem. That creature is the goat.

In antique nomadic rugs, the goat appears not always in figurative form, but in coded visual language — its presence encrypted in stylized horns, geometric bodies, and repeated tribal motifs. While symbols such as the tree of life, the ram’s horn, or the scorpion have long been studied in textile iconography, the goat as a central totem remains surprisingly underexamined.

This article seeks to reintroduce the goat as one of the oldest and most persistent motifs in the tribal weaving arts of the Turkic world — a symbol deeply tied to survival, fertility, strength, and ancestral identity. Drawing from historical references, weaving analysis, and comparative cultural motifs, we will explore how the goat survives not only in pasture but in pattern.

1. The Goat in Nomadic Life and Myth

In the traditional life of nomads — Qashqai, Shahsavan, Karakalpak, Turkmen, and many others — goats were more than livestock. They were the first morning sounds, the first food and wool source for the children, and often the last thing to be fed in times of scarcity. Goats were light-footed survivors, capable of climbing high, enduring drought, and adapting to harsh climates — much like the nomads themselves.

This utilitarian closeness gave rise to sacred symbolism. In Turkic mythology, the goat — especially the horned male — stood for virility, protection, and power. In some epic cycles such as Dede Qorqud, the goat’s horn becomes a marker of male beauty and warrior strength. In shamanic practices, goat skins and horns were used in rituals for fertility and livestock blessing.

In some Oghuz-Turkic cosmologies, the goat is seen as a liminal being — one foot in the natural world, one in the spirit realm — connecting the mountain to the heavens. In this way, it became a potent emblem of spiritual endurance and tribal continuity.

2. Visual Symbolism in Rugs and Textiles

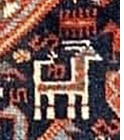

The challenge of the goat symbol lies in its abstraction. In the context of antique nomadic weaving, especially pile rugs, sumak bags, and kilims, the goat is rarely depicted realistically. Instead, it is stylized — fragmented into its most powerful parts: the horn, the chest, the stance.

The most iconic representation is the goat horn motif — a double-spiral, S-shaped or hooked form often mistaken for a ram’s horn. While the ram and goat were sometimes interwoven symbolically, the goat’s horn is often more elongated, branching, and sometimes mirrored, forming symmetrical medallions or central axis patterns. These motifs, seen in Shahsavan sumak panels and Guba rugs, can symbolize masculinity, blessing, and protection.

Another common abstraction is the “standing goat” figure, depicted in kilims or flatweaves with vertical, rectangular bodies and two upright ears or horns. These forms, repeated in bands or borders, often appear in Karakalpak, Uzbek, or Anatolian tribal textiles.

In some weavings, entire compositions are arranged around fertility symbolism: the female goat form is suggested through body motifs paired with lozenges (diamonds) and comb-like elements, alluding to motherhood and milk.

3. Regional Expressions and Totemic Variants

South Caucasus & Azerbaijan: In the Guba and Karabagh regions, antique pile rugs often exhibit highly stylized horned animals flanking medallions — some of these may be goats rather than rams, especially when associated with tribal wedding dowries or child-protection themes. In certain Bordjalou and Shirvan weavings, goat horn spirals are repeated in the outer borders as charms.

Iranian Shahsavan & Qashqai: In Shahsavan sumak bags, the goat horn motif appears as a central vertical totem in mafrash panels. Qashqai women also wove goat motifs into tent bands and ceremonial kilims, often combining them with bird, tree, and comb forms — a full spectrum of life-giving symbols.

Central Asia: Among Turkmen and Karakalpak tribes, goats were associated with winter survival and mobile wealth. Goat motifs appear in felt rugs (shyrdak) and in pile-framed trappings, particularly among non-urban Uzbeks. Some early Yomut and Tekke pieces even suggest goat silhouettes among the gul structures — long overlooked by scholars.

4. Goat Symbolism in Function and Design

Many goat symbols are located in the most protective places of a weaving — the four corners, the center medallion, or the flanking bands — suggesting their apotropaic role (protective magic). In tribal belief, placing the goat symbol at key visual junctures was a means of invoking its spirit: agile, resourceful, and blessed with life-giving milk and flesh.

Additionally, the goat’s abstract presence served a tribal signature function: certain motifs acted as identifiers of clan origin, marriage line, or seasonal migration route. A woven goat horn was not just an aesthetic flourish — it was a statement of lineage and faith.

5. Reclaiming the Symbol Today

In the current antique rug market, few symbols are as misunderstood or misattributed as the goat. Dealers often conflate it with generic ram’s horns, scorpions, or mere decorative spirals. Yet, the deeper reading unlocks a narrative that ties weaving to survival, myth, gender, and land.

By recognizing and naming the goat symbol explicitly, we reclaim a lost layer of meaning. It reminds us that these weavings were not mere decoration, but storytelling devices — portable temples of memory and belief.

In a time when identity and authenticity are prized, bringing attention back to these totemic roots is not only scholarly, but spiritual.

Conclusion: A Living Pattern

The goat, in its humble and sacred form, continues to leap across the warp and weft of nomadic heritage. Whether standing proud in a kilim’s band or curled in the horned spiral of a border motif, it remains a guardian of ancestral wisdom.

As collectors, scholars, and stewards of these rugs, we are invited to look again — more closely, more reverently — at the patterns beneath our feet. For in the dance of symbols, the goat is not lost. It is waiting to be seen.

By Amir Oskouei July 29, 2025

Founder, Amir Textiles & Rugs – Researcher & Collector of Turkic Woven Art